Urdu Poetry Ghazal Biography

Source (google.com.pk)

The ghazal (Arabic/Pashto/Malay/Persian/Urdu: غزل; Hindi: ग़ज़ल, Marathi: गझल Punjabi: ਗ਼ਜ਼ਲ, Nepali: गजल, Turkish: gazel, Bengali: গ়জ়ল, Gujarati: ગ઼ઝલ) is a poetic form consisting of rhyming couplets and a refrain, with each line sharing the same meter. A ghazal may be understood as a poetic expression of both the pain of loss or separation and the beauty of love in spite of that pain. The form is ancient, originating in 6th-century Arabic verse. It is derived from the Arabian panegyric qasida. The structural requirements of the ghazal are similar in stringency to those of the Petrarchan sonnet. In style and content it is a genre that has proved capable of an extraordinary variety of expression around its central themes of love and separation. It is one of the principal poetic forms which the Indo-Perso-Arabic civilization offered to the eastern Islamic world.

The ghazal spread into South Asia in the 12th century due to the influence of Sufi mystics and the courts of the new Islamic Sultanate. Although the ghazal is most prominently a form of Dari poetry and Urdu poetry, today it is found in the poetry of many languages of the Indian sub-continent.

Ghazals were written by the Persian mystics and poets Rumi (13th century) and Hafiz (14th century), the Azeri poet Fuzûlî (16th century), as well as Mirza Ghalib (1797–1869) and Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938), both of whom wrote ghazals in Persian and Urdu, and the Bengali poet Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976). Through the influence of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), the ghazal became very popular in Germany during the 19th century; the form was used extensively by Friedrich Rückert (1788–1866) and August von Platen (1796–1835). The Indian American poet Agha Shahid Ali was a proponent of the form, both in English and in other languages; he edited a volume of "real ghazals in English".

In Urdu, some important and respected ghazal poets are: Mirza Ghalib, Mir Taqi Mir, Momin Khan Momin, Daagh Dehlvi, Khwaja Haidar Ali Aatish, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Khwaja Mir Dard, Jaun Elia, Hafeez Hoshiarpuri, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Ahmad Faraz, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Muhammad Iqbal, Qamar Jalalabadi, Shakeb Jalali, Nasir Kazmi, Sahir Ludhianvi, Hasrat Mohani, Makhdoom Mohiuddin, Jigar Moradabadi, Munir Niazi, Mirza Rafi Sauda, Qateel Shifai, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Wali Mohammed Wali and Mohammad Ibrahim Zauq.

After nearly a century of "false starts" — that is, early experiments by James Clarence Mangan, James Elroy Flecker, Adrienne Rich, Phyllis Webb, etc., many of which did not adhere wholly or in part to the traditional principles of the form, experiments dubbed as "the bastard ghazal" — the ghazal finally began to be recognized as a viable closed form in English-language poetry sometime in the early to mid-1990s. This came about largely as a result of serious, true-to-form examples being published by noted American poets John Hollander, W. S. Merwin and Elise Paschen, as well as by Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali, who had been teaching and spreading word of the ghazal at American universities over the previous two decades.

In 1996, Ali compiled and edited the world's first anthology of English-language ghazals, published by Wesleyan University Press in 2000 as Ravishing DisUnities: Real Ghazals in English. (Fewer than one in ten of the ghazals collected in Real Ghazals in English observe the constraints of the form.)

A ghazal is composed of couplets, five or more. The couplets may have nothing to do with one another, except for the formal unity derived from a strict rhyme and rhythm pattern.

A ghazal in English that observes the traditional restrictions of the form:

Where are you now? Who lies beneath your spell tonight?

Whom else from rapture’s road will you expel tonight?

Those “Fabrics of Cashmere—” “to make Me beautiful—”

“Trinket”— to gem– “Me to adorn– How– tell”— tonight?

I beg for haven: Prisons, let open your gates–

A refugee from Belief seeks a cell tonight.

God’s vintage loneliness has turned to vinegar–

All the archangels– their wings frozen– fell tonight.

Lord, cried out the idols, Don’t let us be broken

Only we can convert the infidel tonight.

Mughal ceilings, let your mirrored convexities

multiply me at once under your spell tonight.

He’s freed some fire from ice in pity for Heaven.

He’s left open– for God– the doors of Hell tonight.

In the heart’s veined temple, all statues have been smashed

No priest in saffron’s left to toll its knell tonight

God, limit these punishments, there’s still Judgment Day–

I’m a mere sinner, I’m no infidel tonight.

Executioners near the woman at the window.

Damn you, Elijah, I’ll bless Jezebel tonight.

The hunt is over, and I hear the Call to Prayer

fade into that of the wounded gazelle tonight.

My rivals for your love– you’ve invited them all?

This is mere insult, this is no farewell tonight.

And I, Shahid, only am escaped to tell thee–

God sobs in my arms. Call me Ishmael tonight.

—Agha Shahid Ali

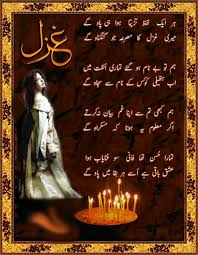

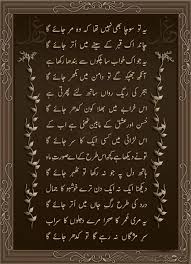

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

Urdu Poetry Ghazal

No comments:

Post a Comment